I. Executive Summary

On June 10, 2021, the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress of China promulgated the PRC Data Security Law (“DSL”), which will come into force on September 1, 2021. The legislative intent for this law mainly includes regulating data processing activities, ensuring data security, promoting data development and utilization, protecting the data related legitimate rights and interests of individuals and organizations, and safeguarding national sovereignty, security and development interests. Notably, Article 36 of the of the DSL explicitly prohibits any organizations or individuals in China from providing data stored within China to foreign judicial or law enforcement agencies unless it is approved by the competent authority of China, a scenario highly related to cross-border Compliance Investigations and Litigations. More importantly, a dual-punishment system is stipulated in Article 48 of the DSL, covering penalties including a fine up to RMB 5 million, suspension of business operation or even revocation of business license on the organizations and a fine up to RMB 500,000 on the persons in charge and other directly responsible persons.

With extensive experience in handling multi-jurisdictional cross-border investigations and compliance projects, the Compliance and Investigation Team of Global Law Office has launched a series of research and studies on the disputed issues encountered in real practice with respect to cross-border compliance and investigations. This article aims to provide more insights on the potential legal implications of the DSL on cross-border Compliance Investigations and Litigations by multinational companies (“MNCs”) in China through analyzing the representative scenarios and to provide corresponding suggestions and recommendations to mitigate the potential legal risks. In terms of any ongoing data provision, we would suggest MNCs to start the preparation for filling applications and suspension of any high-risk data provision. In terms of any potential data provision during cross-border compliance investigations, MNCs would be advised to take preventative measures, which include localizing the investigation efforts, keeping all relevant data in China, and minimizing cross-border data transfer based on necessity. In addition, MNCs are also recommended to strengthen internal control and re-evaluate the global IT infrastructure. As the DSL was newly promulgated, we anticipate that more interpretations and implementing rules on the DSL to be released in a near term, and it is suggested to closely monitor the legislation development with this respect.

This article mainly analyzes the legal implications from DSL’s perspectives while it is still important to note that as cross-border investigations and litigations are frequently implicated with other restrictions on transfer of protected data such as state secrets, intelligence, important data, and personal information etc., under the relevant PRC laws and regulations, comprehensive analysis on all relevant legal issues would be required.

II. Analysis of Key Provisions of the DSL and Its Impacts on Cross-Border Compliance Investigations and Litigations

1. Legislative Development

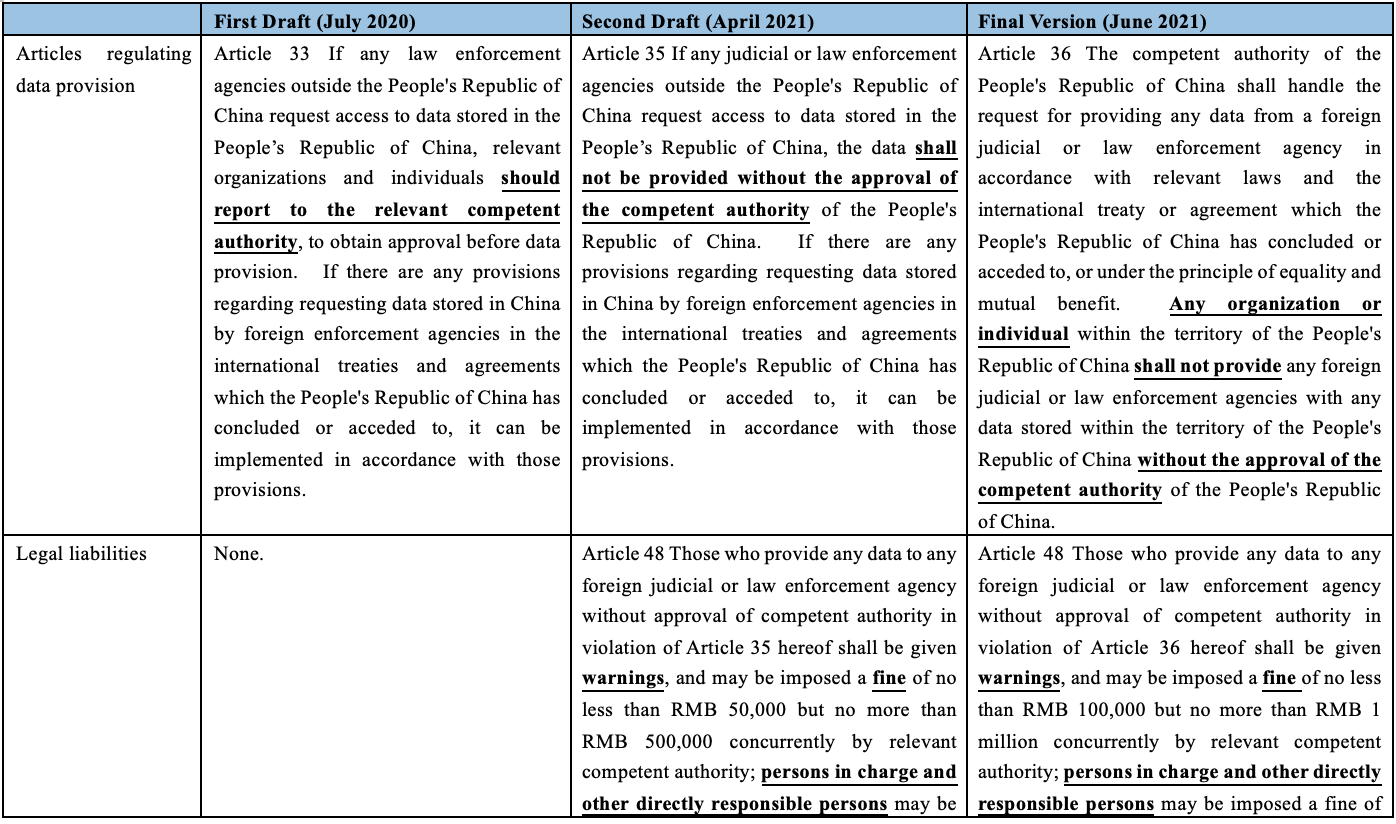

The first draft of the DSL was released on July 3, 2020, and second draft was released on April 29, 2021, respectively. The final version of the DSL was promulgated on June 10, 2021, nearly one month after the release of the second draft. In terms of the provisions regarding providing data to foreign judicial or law enforcement agencies, there have been substantial changes and we have illustrated in below comparison chart for our readers’ easy reference.

2. Application of Key Provisions

Article 36 of the DSL regulates the conduct of providing data stored within China to foreign judicial or law enforcement agencies by organizations or individuals in China and Article 48 of the DSL stipulates the legal liabilities for relevant administrative violations. Upon comparative analysis on the several versions of the DSL as well as other relevant laws such as the PRC International Criminal Judicial Assistance Law (“ICJAL”) and the draft PRC Personal Information Protection Law, more in-depth understandings and interpretations on the key provisions are illustrated as follows.

(1) Scope of Data Being Regulated

Data is defined broadly under Article 3 of the DSL as any record of information in electronic or other forms, which basically means information recorded in any form stored within China shall be subject to this restriction.

Notably, the draft version of the Personal Information Protection Law also proposes to include similar provision to implement pre-approval process before providing personal information stored within the territory of China. Though the final version of the Personal Information Protection Law has not yet been promulgated[1], given that personal information is one type of data under the DSL, we believe that the requirement under the Personal Information Protection Law would generally be consistent with the DSL.

(2) Organizations or Individuals Being Regulated

In terms of the subject being regulated, it refers to organizations or individuals in China. Interestingly, the first draft and second draft of the DSL once proposed to regulate the conduct of providing data without specifying the location of the subject, while the final version of the DSL clarifies the scope of the subject as organizations or individuals in China. The rationale behind it may be related to the considerations for the feasibility and potential obstacles in enforcing this restriction and imposing punishment on extraterritorial organizations or individuals.

(3) Type of Data Recipient

In terms of the recipient of the data under Article 36, it includes both foreign judicial and law enforcement agencies. Although the first draft of the DSL proposed to only regulate data request from foreign law enforcement agencies, the second draft and final version of the DSL added foreign judicial agencies into the scope of data recipient. From a literal interpretation, judicial and law enforcement agencies could cover a wide range, taking the US for example, it could include both state courts and federal courts as well as any executive branch of the US government such as the US Department of Justice (“DOJ”) and the US Securities Exchange Committee (“SEC”). Compared with the ICJAL, which only applies to foreign agencies in criminal proceedings (for detailed analysis, please refer to our previous article “Are Private FCPA Investigations Still Doable in China?”), the DSL would be applied to any judicial and law enforcement agencies in foreign jurisdictions[2].

Moreover, both the first and second draft of the DSL proposed to regulate providing data to foreign judicial and law enforcement agencies upon their request without clarifying whether it is prohibited to proactively providing the data without formal or informal request[3] from such authorities. This issue has been clarified by the final version of the DSL, which removes the condition of request from foreign judicial and law enforcement agencies and simply prohibits the conduct of providing data to any foreign agency without approval from authority in China. In other words, the practices of voluntarily and proactively providing data to foreign authorities during some typical Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (“FCPA”) related cross-border investigations or even financial filing to the SEC are also prohibited without prior approval.

(4) Legal Liabilities

Article 48 of the DSL provides that violation of Article 36 would lead to warnings by the competent authorities and a fine ranging from RMB 100,000 to 1 million to organizations, as well as a fine ranging from RMB 10,000 to 100,000 to persons directly in charge and other directly responsible persons; where serious consequences are caused (subject to further interpretations but usually involves national security, social security and public interests), a fine ranging from RMB 1 million to 5 million shall be imposed, and the organization may be ordered to suspend the relevant business, suspend the operation for rectification, and the relevant business permit or business license of the organization may be revoked; persons directly in charge and other directly responsible persons shall be subject to a fine ranging from RMB 50,000 to 500,000.

Notably, in the first draft of the DSL, there was no provision containing legal liabilities for providing data to foreign judicial or law enforcement agencies without approval. And in the second draft of the DSL, a proposed provision for legal liabilities included a fine up to RMB 1 million on the organizations and RMB 20,000 on the persons directly in charge and other directly responsible persons[4]. In comparison, the final version of the DSL substantially increases the penalty amount to RMB 5 million and includes implications on business operation to impose more deterrence on such violation, indicating strong determination of the Chinese government on prohibiting illegal data provision as well as actual enforcement. When the ICJAL was promulgated in October 2018, there were a lot of discussions regarding the non-inclusion of penalty terms, mainly for the concerns for lack of teeth for Article 4, which states that organizations and individuals within the territory of China shall not provide evidence materials and assistance provided in this law to foreign countries, without the consent of the competent authority of China. Although in practice, there have been some formal or informal applications made by the companies to the authority for submitting materials and evidence to foreign authorities, enforcement on this article still relies on companies’ proactive reporting instead of post-event punishment. Nevertheless, after the DSL comes into effect, more real and visible enforcement actions from both proactive and reactive perspectives are anticipated to be taken by the authorities.

In terms of individual liabilities, as Article 48 of the DSL does not specify the scope or position of “persons directly in charge and other directly responsible persons”, it then leaves more space for interpretation. From data security perspective, persons directly in charge and other directly responsible persons may include anyone assigned to be responsible for cybersecurity and data security within the company as well as those in charge of the specific cross-border data transfer programs during compliance investigations or litigation. Relevant positions at risk include but not limit to IT manager, data protection officer, compliance and/or legal head, or any other senior leadership positions who make the final call of providing the data.

3. Analysis on Representative Scenarios

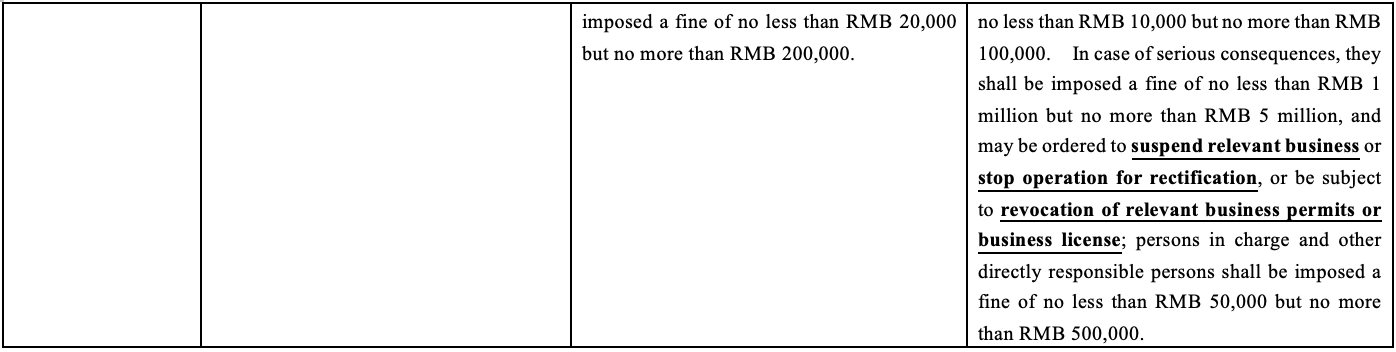

Based on the above analysis, while there remain a few gaps in the DSL with regard to the implementation of Article 36 and 48, including the designated authority for enforcement and the regulatory approach that the authority would take, it would still be advisable for MNCs in China to conduct proactive risk assessment with this respect. To facilitate our readers’ understanding, we have selected a few typical scenarios in real business operation for further analysis. The main factors under consideration include 1) location of the data; 2) which party controls the data; and 3) which party provides the data to the foreign judicial or law enforcement agencies.

(1) Data Stored in China, IT infrastructure Controlled by China Entity

a. Data provided by China Entity

For MNCs with headquarters based in China, the IT infrastructure would usually be governed and controlled by the China entity, with servers located in both China and/or foreign countries. Due to the possible data localization requirements and/or data export control restrictions of some foreign jurisdictions, it is a common practice that the data collected and generated by the China entity would be stored in servers located in China, and data collected and generated in foreign jurisdictions would be mainly stored in servers located in foreign jurisdictions, while occasionally, data generated in foreign jurisdictions would also be collected and stored directly in servers located in China.

Under circumstances where data stored in China (regardless of where the data is generated) needs to be transferred to foreign jurisdictions, typically during cross-border litigations (particularly for IP litigations where a sizable amount of data is required) and financial reporting (for instance, chief executive officers and chief financial officers of US listed companies are required to make attestations on the accuracy and reliability of the financial information and conduct periodic reporting of the internal control effectiveness to the SEC disclose under the section 302 and 404 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act), such data transfer would be subject to the approval from the Chinese authority. And if the China entity provides the data to the foreign judicial or law enforcement agencies without prior approval, it would be deemed as a violation of Article 36 of the DSL.

For MNCs with headquarters based in foreign jurisdictions, if the IT infrastructure related to the data stored in China is governed and controlled by the China entity, then the same analysis as above would be applied here. Under the circumstances where data stored in China needs to be transferred to foreign jurisdictions, typically during cross-border compliance investigations related to FCPA and export control, it would be important to pre-assess the likelihood of the involvement of foreign judicial or law enforcement agencies. Wherever there is any indicator of involving any foreign judicial or law enforcement agencies, such as inclination for self-disclosing or cooperation in foreign government investigation, then even if the data has already been transferred from China to foreign jurisdictions, approval from the Chinese authority would still be required before providing the data to foreign judicial or law enforcement agencies. And if the China entity provides the data to the foreign judicial or law enforcement agencies without prior approval, it would likely be deemed as a violation of Article 36 of the DSL.

b. Data Provided by Foreign Entity

If it is not the China entity that provides the data to foreign judicial or law enforcement agencies, instead, the foreign entity directly collects and provides the data stored in China to foreign judicial or law enforcement agencies, then the legal liabilities for the China entity may depend on its involvement in the data provision with the factors such as whether the China entity exercises any level of control over the data, whether the China entity has knowledge about the data provision and whether the China entity consents to the data provision. Under the circumstances where the IT infrastructure is governed and controlled by the China entity, there would be a natural assumption that the China entity is more or less involved in the data provision, such as granting data access to the foreign entity or at least has knowledge about the data collection and provision. Correspondingly, the China entity would possibly be subject to the legal liabilities due to its involvement in the data provision.

(2) Data Stored in China, IT infrastructure Controlled by Foreign Entity

a. Data provided by China Entity

Same as above, for a China entity that provides the data to foreign judicial or law enforcement agencies (regardless of directly or through the foreign entity) without approval from the Chinese authority, it would likely be deemed as a violation of Article 36 of the DSL.

b. Data provided by Foreign Entity

As discussed above, if the foreign entity directly collects and provides the data stored in China to foreign judicial or law enforcement agencies, then the legal liabilities for the China entity may depend on its involvement in the data provision with the factors such as whether the China entity exercises any level of control over the data, whether the China entity has knowledge about the data provision and whether the China entity consents to the data provision. Under the circumstances where the IT infrastructure is governed and controlled by the foreign entity, if the data provision is conducted in the name of the foreign entity but known and assisted by the China entity, then the China entity would likely be subject to the legal liabilities due to its involvement in the data provision. Nevertheless, if the data provision is conducted purely by the foreign entity without any linkage to the China entity, then the risk for the China entity would be uncertain, subject to further clarifications from the relevant authorities.

(3) Data Generated in China but Collected and Stored in Foreign Jurisdictions

Generally speaking, Article 36 of the DSL only applies to data stored in China and does not regulate data that is generated in China but directly collected and stored in foreign jurisdictions. For example, in practice, many MNCs use third-party whistle blower and investigation case management software or web solutions, and the data is collected and stored in servers located in foreign jurisdictions. Under such circumstances, it is possible that such data would be accessed by foreign law enforcement agencies due to its relevancy to certain enforcement cases or compliance programs. Although this scenario would likely not be subject to Article 36 of the DSL, MNCs would need to conduct further assessment on whether other types of protected data are involved to ensure compliance with relevant PRC laws and regulations.

III. Implication and Preliminary Compliance Suggestions

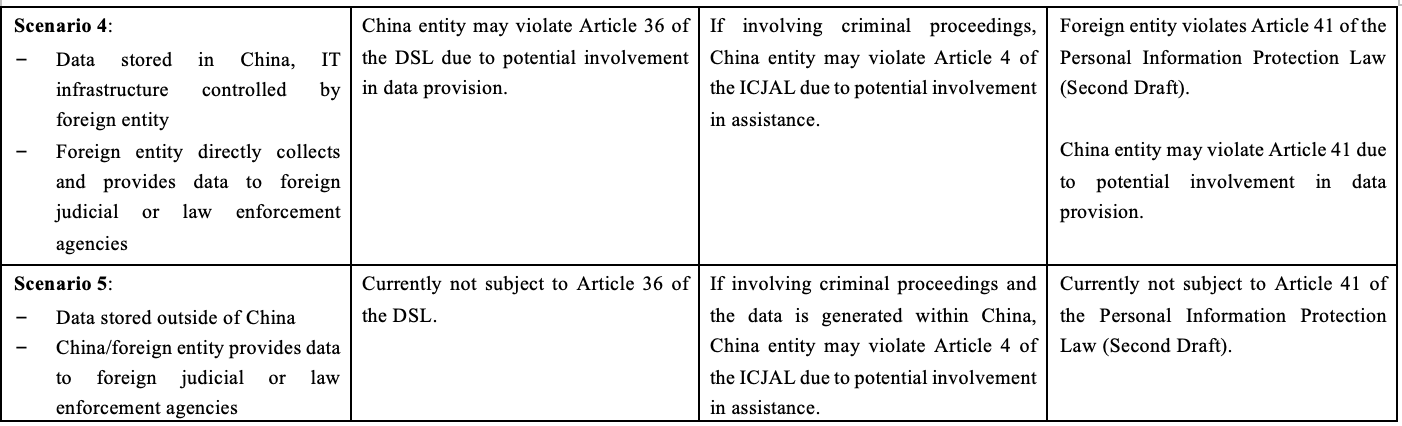

For majority of the MNCs in China, as data provision to foreign judicial or law enforcement agencies is sometimes inevitable in real life daily operation, typically for making a routine periodical financial reporting or fulfilling certain investigation cooperation obligations, it is critically important to identify the risks and take remediation measures accordingly (we have prepared a comparison chart as Appendix I regarding the risks for different scenarios under the DSL, ICJAL and second draft of the Personal Information Protection Law). Moreover, we have also listed a few preliminary suggestions on how to conduct cross-border compliance investigations compliantly according to the DSL for our readers’ quick reference.

1. For Any Ongoing Data Provision——Preparation for Filing Application or Suspension of Data Provision

Although the detailed implementation rules for the DSL have not been released, it is estimated that the requirements for such application would be clarified in a near term for the Chinese authority to enforce Article 36 and 48. Before that, it is suggested that MNCs could start the preparation for such applications during a cross-border compliance investigation from the following perspectives including:

1) Conduct data review and filtering to ensure no sensitive data would be provided to foreign judicial or law enforcement agencies;

2) Minimize the scope, type, and size of the data to ensure the necessity of the data provision could be reasonably justified;

3) Assess the potential consequences for the data provision to ensure no harm to the national security, public interests, or legitimate interests of any other individuals or organizations.

If, after internal assessment, the legal risk of ongoing data provision to foreign judicial or law enforcement agencies is relatively high, then immediately suspension of such data provision is highly recommended!

2. For Any Potential Data Provision——Taking Preventative Measures

In terms of any internal investigations or reviews that may potentially involve or lead to data provision to foreign judicial or law enforcement agencies, it is suggested to take some preventative measures from the very beginning of the investigation. One of the suggestions is to localize the investigation efforts and keep all relevant data in China before any clear guidance is released.

Another suggestion is to minimize the transfer of data stored in China to foreign jurisdictions, for example, only providing highly summarized information for internal reporting purposes to mitigate risks and to ensure such information sharing is necessary and conducted in a reasonable manner without violation of any Chinese laws, given that the DSL does not prohibit cross-border communications and brief sharing for management and internal control purposes within a corporation.

Lastly, for the data that is transferred to foreign jurisdictions for internal information sharing, before it is provided to any foreign judicial or law enforcement agencies by the foreign entity of a MNC either proactively or upon request, it is important to conduct thorough assessment to mitigate the risks for the China entity’s being held liable for any involvement of providing the data foreign judicial or law enforcement agencies without prior approval from the Chinese authority.

3. For Data Provision Mechanism——Strengthening Internal Control and Re-evaluating Global IT Infrastructure

Measures for internal control on cross-border data transfer and data provision are suggested to be designed and implemented. Particularly, an internal control step to assess whether the data to be provided to foreign judicial or law enforcement agencies includes any data stored in China could be integrated into the existing internal process. In addition, it is also recommended to enhance intra-group communications with this respect to avoid inadvertent data provision.

In addition, as data transfer/sharing with third-party vendors or business partners is also inevitable in daily business operation, adequate control on those parties regarding data processing and data transfer would also need to be exercised through proper contractual agreements or periodic auditing to mitigate potential risks.

Moreover, after reading Article 36 and 48 of the DSL, an instant reaction of some MNCs is to relocate the servers outside of China to circumvent the approval process as stipulated. While it is not prohibited by the PRC data protection laws, whether this approach is feasible would still be subject to a various of data localization requirements and security assessment requirements imposed by the PRC data protection laws. For instance, for some types of protected data, such as healthcare big data, population health data, important data, or personal information for certain industries, data localization needs to be fulfilled as a general requirement. Therefore, it would be suggested to conduct a data mapping of the data categories, data location, and any specific requirements on data storage and transfer before any substantial change on global IT infrastructure.

IV. Conclusion

Based on above analysis, while there remain a few gaps in the DSL with regard to the implementation of Article 36 and 48, a clear trend for more real and imminent enforcement actions is anticipated. All these have imposed challenging requirements on MNCs to evaluate the regulatory requirements in different jurisdictions, to identify and control risks and to operate business in a legal and compliant manner. Our suggestion is to keep a close eye on any development of the law and its implementing rules, adopt a relatively cautious and conservative approach for interpretation. In addition, for those matters involving complex issues or more delicate situations, professional legal support should be sought in a timely manner.

Appendix I:

Reference:

[1] Article 41, Second Draft of the PRC Personal Information Protection Law(《个人信息保护法(草案二次审议稿)》), “if any judicial or law enforcement agencies outside the People's Republic of China request access to personal information stored in the People’s Republic of China, the data shall not be provided without the approval of the competent authority of the People's Republic of China. If there are any provisions regarding requesting data stored in China by foreign enforcement agencies in the international treaties and agreements which the People's Republic of China has concluded or acceded to, it can be implemented in accordance with those provisions.”

[2] Article 2, International Criminal Judicial Assistance Law of the People's Republic of China (《中华人民共和国国际刑事司法协助法》), for the purpose of this Law, “international criminal judicial assistance refers to the assistance provided mutually between the People's Republic of China and foreign countries in such activities as criminal inquiry, investigation, prosecution, trial and execution, including the service of documents, investigation and evidence collection, arrangement of witnesses to testify or assist in investigations, seizing, detaining, or freezing the property involved, confiscate or return illegal income and other property involved, transfer the sentenced person, and other assistance”.

[3] Article 35, Second Draft of the PRC Data Security Law(《数据安全法(草案二次审议稿)》), “If any judicial or law enforcement agencies outside the People's Republic of China request access to data stored in the People’s Republic of China, the data shall not be provided without the approval of the competent authority of the People's Republic of China. If there are any provisions regarding requesting data stored in China by foreign enforcement agencies in the international treaties and agreements which the People's Republic of China has concluded or acceded to, it can be implemented in accordance with those provisions.”

[4] Article 46, Second Draft of the PRC Data Security Law(《数据安全法(草案二次审议稿)》), “violation of Article 35 of this Law, without the approval of the competent authorities to provide data to foreign judicial or law enforcement agencies, the competent authorities shall order correction, give a warning, and may impose a fine of not less than RMB 100,000 and not more than RMB 1 million, the directly responsible supervisors and other directly responsible personnel may be fined not less than RMB 20,000 and not more than RMB 200,000.

-

业务领域: Life Science & Healthcare、Compliance & Risk Control、Corporate / Merger & Acquisition、Private Equity & Investment Funds、Environment, Social & Governance (ESG)

业务领域: Life Science & Healthcare、Compliance & Risk Control、Corporate / Merger & Acquisition、Private Equity & Investment Funds、Environment, Social & Governance (ESG) -

业务领域: Compliance & Risk Control、Anti-trust & Competition、Life Science & Healthcare、Dispute Resolution、Environment, Social & Governance (ESG)

业务领域: Compliance & Risk Control、Anti-trust & Competition、Life Science & Healthcare、Dispute Resolution、Environment, Social & Governance (ESG)